Sri Lanka Tea

When Coffee was King

Strange as it may seem, the story of Ceylon Tea begins with coffee. The tale begins in the early 1820s,

barely five years after the surrender of Kandy, the last surviving indigenously-ruled state in Ceylon, to

the British crown. By then, the rest of the island had already been a British colony for more than a

generation. Its possession was considered vital to imperial interests in India and the Far East, but the

cost of maintaining the military presence and infrastructure necessary to secure it was prohibitive.

Attempts to raise revenue by taxation could not by themselves fill the gap; how to make the colony pay

for itself and its garrison was a problem that had troubled successive governors since the first, Frederic

North, took office in 1798.

Tea Saves the Day

The early 1880s were a lean time in Ceylon. The colonial economy had been built almost entirely on the

coffee enterprise, and when the enterprise collapsed, so did the economy. Plantations ‘up-country’

were sold for a song, while in Colombo there were runs on the banks. Frantic experiments with indigo

and cinchona came to naught. The Planters’ Association presented the government with panic-stricken

proposals for administrative retrenchment – which were, fortunately, rejected. An aura of panic settled

over the colony.

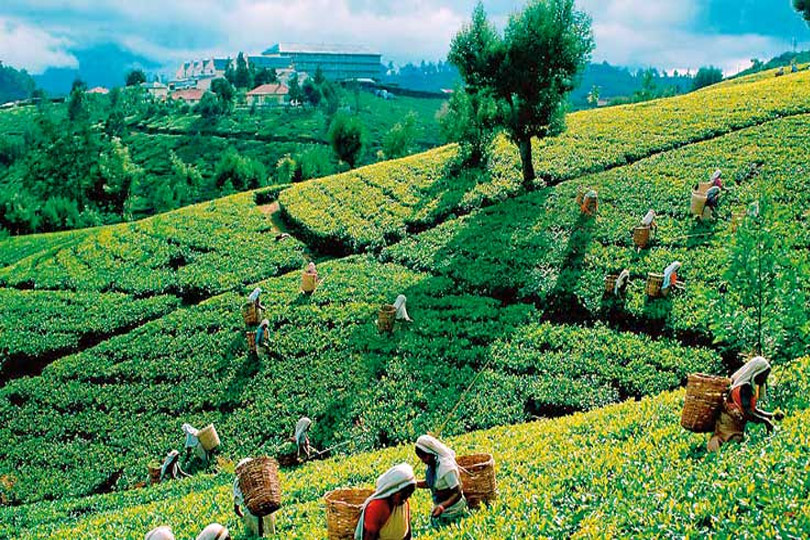

Mature Industry

Following the collapse of the coffee industry, a great consolidation of ownership took place on the

estates of Ceylon’s hill country. The early coffee planters had been, for the most part, sole proprietors,

though some also worked as estate-managers for British civil servants, military officers and church

functionaries who had bought plantation lands during the rush of the 1840s but were unable to attend

to the management themselves. When blight brought the enterprise low, many of these proprietors

sold out, often for a quarter or less than their recent value. The result was larger estates, or ‘groups’ of

estates, belonging to fewer owners.

Independence and After

Ceylon became independent on 4 February 1948. At first, the impact of this momentous event on the

tea industry was negligible. Difficulties arose concerning the citizenship of Indian workers living on the

plantations, but this did not greatly affect output. Indeed, Ceylon had, by 1962, become the biggest tea

exporter in the world.